ARCHITECTURAL

FUSION AND INDIGENOUS IDEOLOGY

IN

EARLY

COLONIAL TEPOSCOLULA

A

Paper to be Presented at the

48TH

INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF AMERICANISTS

"THREATENED

PEOPLES AND ENVIRONMENTS IN THE AMERICAS"

Stockholm,

Sweden

4-9

July 1994

SYMPOSIUM:

LATIN AMERICAN COLONIAL ARCHITECTURE AND URBANISM ON THE FRINGES

SUB-TITLE

OF PAPER:

The Casa de la Cacica, Teposcolula, Oaxaca, Mexico: A Building at the

Edge of Oblivion.

©

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

Número 66 México 1995

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

Reprinted

by kind permission of the editors.

see also

http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/redalyc/pdf/369/36906602.pdf

ARCHITECTURAL FUSION IN COLONIAL MEXICO:

INDIGENOUS LEADERSHIP

Documentary evidence and

standing buildings show that from an early date indigenous leaders in various

parts of colonial Mexico were systematically manipulating elements of the

incoming European architecture in a deliberate fusion with well known elements

of pre-contact form culture, consciously creating new, distinctive, high status

building types. In several cases the evidence demonstrates clear ideological and

symbolic motives. In these cases, and especially in Teposcolula, the evidence

shows that the implementation and integration of the ideological program was not

limited in its conception to a single high status building in isolation, but

rather was carried out at the level of the initial urban planning of the new

colonial towns, and recognizing important relationships within the overall

sacred landscape. In Teposcolula and elsewhere, then, the evidence shows that

the indigenous leadership participated in the process of urban planning,

successfully transmitting important elements of their traditional culture into the new era as permanent and

highly visible components of their new built environment. This process of fusion

of indigenous and European architectural forms and technologies resulting in new

building types such as seen in the Casa de la Cacica in Teposcolula was arrested

by the terrible epidemic of 1576. The devastating, demoralizing and

destabilizing consequences of the demographic collapse sapped the vitality of

this new architecture and rather than flourishing and flowering it died and

decayed, leaving us but a few reminders of a hopeful moment in the history of

cultural transmission and transformation in early colonial Mexico.

PRE-CONTACT PRECEDENTS: HIGH STATUS ARCHITECTURE IN THE CODICES

Before proceeding to a discussion of early colonial fusion architecture,

a brief review of some traditional indigenous building types is in order. Most

pre-contact examples of picture writing were destroyed during the early years of

the colonial era, however the surviving documents provide numerous examples of

buildings depicted in a stylized form. Of various possibilities, selections from

three screenfolds from the Mixtec cultural zone--the Codex Vindobonensis

Mexicanus I, the Codex Nuttall, and

the Codex Sánchez Solís--sufficiently illustrate typical pre-contact graphic

representations of high status

buildings.1

While these and other examples of screenfold illustration have in common

a high degree of stylization, the technique is nevertheless capable of

distinguishing and differentiating between several types of structures including

steam baths, high status residences

and temple platforms. Furthermore, an important distinguishing

feature of all buildings is a carefully rendered ornamental frieze. These

friezes usually appear along the top of flat roofed residential buildings, and

sometimes at the crest of steeply pitched thatched roofs. They are also present

on temple platforms both immediately beneath the top surface of the platform and

often also appearing on the small buildings on top of the platform. In the case

of steam baths these friezes occur as in the case of residential buildings,

along the top. No one can say with

certainty exactly what these friezes were intended to communicate, however the

great care with which they were drawn, the

great variety of distinctive patterns employed in diverse combinations with

subtle differences in color combinations of repeated forms strongly suggests

that they carried a specific

meaning easily recognized by those initiated into the complex symbol system.

Because, for the most part, these Mixtec screenfolds were concerned with

genealogy and the relationship of particular families to particular places at

particular times, these friezes may have served a heraldic function, so that

together with specific place glyphs and year glyphs it would be possible to

identify the changes of geneology over time as related to place.

The recording and preservation of this kind of knowledge was, no doubt,

quite important to a landowning elite group, entrance to which was restricted to

legitimate children of parents of recognized lineages on both sides. These

friezes are such prominent features of the architecture as portrayed that it is

natural to assume that the buildings represented actually resembled the graphic

depiction and that these buildings

actually had friezes prominently displaying these same patterns and

communicating the same kind of information to those who saw them.

It is also possible that the information communicated was understood more

precisely by those initiated into what may have been a somewhat esoteric symbol

system, capable of being read at several levels, but denoting at the most basic

level of understanding a high status building. It is believed that the Mixtec

elite reserved for their private use a spoken language not understood by the

common people. 2

EARLY COLONIAL FUSION: EVIDENCE FROM THE DOCUMENTARY RECORD

There are numerous examples of pre-contact building types depicted in

documents prepared in the early colonial period either at the initiative of

indigenous leaders making cases before the colonial judicial system or at the

initiative of colonial officials seeking documentation for administrative or

historical purposes. Donald Robertson wrote on the topic of these early

manuscripts and presented two documents with special relevance here.3

The Codex Mendoza was created at the order of the first Viceroy, don

Antonio de Mendoza, as a background history intended for the King in Spain. Work

began on this historical pictorial in 1541 by a native master painter, Francisco

Gualpuygualcal. Important here is

the retrospective portrayal of Montezuma's palace which had been destroyed

during the conquest. This document is in itself an example of artistic fusion of

traditional Aztec painting style with the new European techniques. Folio 69r

shows Moctecuzoma sitting in his obviously high status pre-contact building.4

The tell-tale disk frieze is, again, the most evident ornamental feature.

The architectural transformations resulting from this fusion of two alien

traditions may also reflect some modifications in the role of the indigenous

leaders in the operation of government in the colonial regime. The Florentine

Codex, compiled by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún

before 1585, gives specific examples of architectural types in

illustrations elaborated by text. In Book 11-Earthly Things Twelfth Chapter,

Ninth Paragraph "which telleth of the various manners of houses [and] their

classifications," there is a text referring to an illustration numbered 889

describing "Tlatocacalli, House where the lord usually lived. This is the

house of the ruler or of him who is esteemed. It means a good, fine, cherished,

proper house." The illustration shows a house with a frieze of discs set in

a dark field, such as those seen on Montezuma's house and on the Tecpan of

Mexico.5

Of course, this book was compiled in the 1580's from accounts of

informants who may not have been old enough to recall events and buildings

pre-dating the conquest, and who

may have been more than a little acculturated after long years of study and work

with the Spanish friars. Still, the accounts and illustrations representing an

indigenous view on the Aztec history and culture before contact are generally

accurate. Furthermore, in the specific case of the architectural use of disk frieze

ornament, the evidence presented in the Florentine Codex is corroborated by

numerous other early colonial and pre-contact sources as we have seen above. The

specific refinement of knowledge offered by this passage in the Florentine Codex

is that buildings in which the ruler lived were of a type that had a special

name, "Tlatocacalli,"

which described this special class or type of building, notable because it was

"... a good, fine, cherished, proper house." And the most notable

visual feature of the building in the illustration is the disk frieze. There was

clearly an association of the ruler, "or him who is esteemed," with a

particular and appropriate type of

special building in the pre-contact world.6

In the colonial regime the role of the indigenous "Lords" or

seigneurs changed from perpetual hereditary dynastic rule to a more democratic

system of elected "Gobernadores" and "Alcaldes" in which the

occupants of the seats local of power rotated periodically among members of the

traditional leadership. While this changed gradually during the sixteenth

century as access to these elected positions became less restricted, at the

outset it was typical for the traditional leaders to be "elected" to

the position of Governor or Alcalde Mayor, unless the colonial administration

found the traditional hereditary leader to be objectionable for one reason or

another.

The mechanism of government forever changed after the conquest, and by the end of the sixteenth century the indigenous leaders

found themselves no longer the undisputed possessors of pre-eminent hereditary

power, but rather holders of posts with a more diluted, bureaucratized authority

institutionalized by the colonial administration. While individuals continued to

hold the posts and exercise the power, it was now the exercise of an

institutional power in which they participated rather than a personal power

exercised on their own authority. This had direct consequences for the

architectural expressions of power. In the past the locus of power was the

dwelling place of the lord, but in the colonial regime it became the seat of the

municipal institutional authority, the Tecpan, or cabildo.

George Kubler stated that "The physical remains of early colonial

Indian housing are difficult to identify. Their form probably persists in such

towns as Mizquic and Milpa Alta. The dwellings of only the Indian nobles and

officials approximated European types."7

However, while it is certainly true that the Indian nobles selectively

incorporated notable European architectural features in their buildings, even

more important was the systematic inclusions of traditional pre-Hispanic forms

and symbolic ornaments. Dr. Kubler adds that "In Texcoco, the Indian nobles

preserved their traditional symbols of prestige. No Indian who pretended to

social distinction in 1582 could afford not to live upon a terreplein (cf. fig

81 [which shows the Tecpan of Mexico in the Codex Osuna]). Small his

house might be, if only enthroned upon an earthen platform."8

Certainly the principal structure in the image Dr. Kubler cites is

elevated as he points out. But what he does not mention may be an even more

important "traditional symbol of prestige:" the disk frieze as plainly and deliberately evident in the

carefully drawn picture as it no doubt was in the real building

portrayed.

Codex Osuna (click on the image to enlarge here and below)

Codex Osuna (click on the image to enlarge here and below)

As Robertson points out, the Codex Osuna was

made between January and August 1565

to present evidence in the

1563-66 Visita by Valderrama

reviewing the government of Viceroy Luís de Velasco.

In this document indigenous leaders claimed non-payment of numerous

services rendered by their people in building construction and

other activities undertaken for the Viceroy. Of special interest is the

representation to which Dr. Kubler referred, found in Document VII, folio

500/38r showing the "tecpan or municipal building of Mexico, `Tecpa'

calli Mexico.'" 9

Here, again, is an explicit documentary depiction of a high status

building, of early colonial construction (before 1565) shown with the same kind

of disk frieze seen on Montezuma's house in the Codex Mendoza as well as on

buildings in the pre-contact codices. Other architectural features typical of

buildings seen in the pre-contact documents include the rectilinear door

openings with the distinctive overhanging lintels. But what is also clearly

evident is the use of distinctly European technology and design in the repeated

use of compression arches seen in the arcade along the front of the building and

especially in the main atrio portal in which the voussoirs are emphatically

rendered with architectural precision. The Codex Osuna is itself a fusion of

pre-contact art forms and picture-writing

systems with European artistic techniques and alphabetically written language.

What it shows in this illustration is an example of a new building type in which

traditional pre-contact forms are deliberately fused with unmistakably European

forms and technologies.

This building so carefully portrayed in the documentary record is an

outstanding example of the design and construction of a new architecture which

had never existed before European and Mesoamerican cultures came into contact.

It was conceived and built as an architectural statement implementing an

indigenous political agenda. The Codex Osuna is a document painstakingly

prepared at the direction of the indigenous leadership specifically for use in a

judicial process at the highest level of colonial administration. The building

depicted was the seat of indigenous municipal authority, and was constructed to

demonstrate and dignify this legitimate indigenous political power within the

new colonial regime. Its careful graphic representation in this high level

document was intended to transmit that demonstration and impart its authority

and dignity into this legal process. The Tecpan of Mexico beautifully recorded

in the Codex Osuna was a building intended to be a lasting architectural

expression of the legitimate power and authority of the indigenous leaders,

demonstrating not only their continuing role as transmitters of the traditional

culture but also their new role as interpreters and transducers of the new

culture. The new architectural forms that emerged at their direction as

permanent and highly visible elements of the new built environment demonstrated

their ability as cultural and political leaders to successfully perpetuate and

integrate their culture into the new world order in early colonial Mexico.

Perhaps the most spectacular

example of early colonial Indian civil architecture survives not only in

Documentary evidence but also in a standing fragment of an original arcade of

the Tecpan of Tlatelolco, begun in 1576. As Kubler said: "It was entirely

an Indian enterprise, built to maintain the dignity of Indian town

government."10

It is worth noting Kubler's observation of the perceived need--lavishly

expressed by this most unusual building--to maintain the dignity of the town

government, as an institution, rather than that of a particular individual. This

extraordinarily luxurious complex, over six hundred feet long in all, included a

suite of 19 rooms, itself 170 feet long and arranged around an elaborate garden,

especially dedicated to the entertainment of the Viceroy and other high status

visitors. The compound also included special facilities for the various elements

of town government, including rooms for scribes, a community room, apartments

for less distinguished travelers, a

jail (on two floors), a separate latrine, a separate bath-house, and all served

by a fresh water system. Kubler details the expense of this undertaking which

totaled 33,600 pesos, of which 5,600 were paid in cash by the Indian elite, the

rest in labor and in kind by the community. He points out that this was on a par

with the well known sale price paid in 1562 by the Crown for the casas nuevas

originally built by Cortes himself.11

Nor were the Tecpans of Mexico and

Tlatelolco isolated instances of high status construction by Indian nobles in

the new colonial environment, for as Dr Kubler points out the Indian leaders

were busy with their own domestic architecture as well:

In 1554, the Indian governor of Tlateloco lived in handsome houses

fronting upon the main plaza. The Indian governor of Coyoacan in 1560 enjoyed

the services of ten brick layers and masons, for the building and maintenance of

his house, which when built was to face upon the main plaza and market.12

Clearly, then, the indigenous leaders were actively engaged in building

not only suitable new municipal offices befitting their traditional dignity, but

also suitable personal residences for themselves. Both were purposefully

integrated into the appropriate locations in the new colonial built environment.

This distinction between the residence of the Indian lord and his municipal

office may reflect the change in the nature of government: in pre-colonial times

the local lord was the hereditary ruler for life, whereas in the colonial regime

the office of gobernador was--at least officially--an elected position subject

to change at the end of the

predetermined term at the pleasure of those eligible to vote. What these two

types of colonial buildings have in common, however,

is that both were locations associated with persons of high status: one

for private residential use and one for public, official, and ceremonial use,

functions which may have occurred under one roof in pre-colonial times.

Furthermore, the nature of the role of the colonial Indian Governor in

public ceremonial life had no doubt

also changed considerably, especially as this related to religious ritual

performance. In the colonial era public official ceremonial duties might include

lavish entertainment of the Viceroy in specially built and luxuriously furnished

rooms and gardens, but the era in which these Indian lords or caciques

publicly presided over official religious ceremonies had come to an end. In the

new regime these sacramental functions were reserved for the archbishops,

bishops, priests and friars. Of course, membership

in religious confraternities was open to the Indian leaders, an opportunity in

which they often took full advantage.13

Still, it was not the same pre-eminent relationship to the religious ceremonial

life as before. This, no doubt, presented a problem for the native leaders in

the public perception of their status in religious affairs. However, as in the

case of the residential and municipal buildings already noted, there was an

architectural solution to this problem of perception.

EARLY COLONIAL FUSION: RELIGIOUS BUILDINGS

Atotonilco de Tula, Cemetary Chapel

Atotonilco de Tula, Cemetary Chapel

A striking example of the Disk Frieze ornament on an early colonial

religious building occurs at the Cemetery Chapel in Atotonilco de Tula, Hidalgo,

which was probably built in the 1540's but is now in ruinous condition.14 In this case the Disk Frieze is used only on the principal

facade, and displayed originally five red Disks in a field of white mosaic stone

surrounded with a matching red border. There is a flower motif carved into the

disks in this case with eight petals with a clearly defined pair of rings, the

inner most perhaps again composed of smaller petals. These disks are different

from those seen in the Codex Osuna and Codex Mendoza in that they display

clearly carved flower petals, perhaps of a dahlia, a favorite among noble Indian

connoisseurs, including Montezuma.15 There was, in pre-hispanic

times, an association with the cultivation of flowers for pleasure and high

social status.16Fernando

de Alva Ixtilxochitl's account here has the air of an informed observer, he may

be recording a living memory of the event. Certainly the particular distinctions

of the types of flowers and the lavish use of flowers is most interesting, and

relevant to this discussion of the deliberate use of flower imagery on early

colonial buildings. As we have seen in the numerous examples already cited,

there was also in pre-hispanic times a clear association of the disk frieze on

buildings with particular high status individuals. The continuation of these

associations of individuals with buildings expressed by the disk frieze ornament

in early colonial architecture was, no doubt, intended to perpetuate the

ideological message, in this case

linking a native lord with a new Christian temple. In this way, even if it was

no longer possible to publicly preside over the religious ritual performance,

still there was a permanently visible stamp of high status association openly

and obviously linking the Indian leader with the new temple. The church yard is

now surrounded with a high wall, and is so filled with graves that in some cases

they seem to be piled one on top of another, evidently still a prestigious, and

preferred place for burial.

The chapel at Atotonilco de Tula is but one example of this kind of use

of the pre-Hispanic disk frieze on early colonial Christian churches. Among the

standing examples are San Juan Nepopualco, Morelos, in which a frieze of large

double concentric ring disks, like those on Montezuma's house, are still clearly

visible, painted on the original, but now crumbling stucco. Near by two other

examples of the double concentric ring disks show up on early Christian

buildings: virtually identical painted disks in the cloister at Yecapixtla and

in sculptural form on the tower at Totolapan. Another example closer to

Atotonilco in the northern Valley of Mexico may be seen at Tequixquiac, Mex. on

the bell tower, here set in mosaic field with border as at Atotonilco de Tula.17 There are also

examples of the use of disk frieze ornament on churches and chapels in

the documentary record, see for example the place sign of Amusgos on the Lienzo

of Zacatepec. 18

EARLY COLONIAL FUSION: THE MUNICIPIO OF TLAYACAPAN

Another, slightly less obvious, use of the Disk Frieze survives in

fragmentary form at the Municipal Palace located on the Plaza of Tlayacapan in

Morelos, where an incomplete row of disks appears along the top of the building,

alternating between an eight petalled flower and a disk composed of two

concentric rings. The disks emerge from the white-washed wall which becomes

thicker just below the frieze, suggesting a build up of layers of replastering.

This later resurfacing may also be covering the moasic field characteristic of

Atotonilco de Tula and Tequixquiac. While the frieze is incomplete, there is a

double concentric ring lower on the wall near one of the windows.

According to the President of the Municipality, this building was built

before the well known Augustinian convento next door and was used as a temporary

residence for the friars who moved to the convento when it was completed. Then

the building was used as the Cabildo for the local government, according to the

President. Of course, the local government, or Cabildo would have been composed

of the cacique and the principales of the area. The convento dates from 1555,

and Kubler says that the Augustinians took up residence in Tlayacapan in 1554.

Certainly the surviving frescoes in the vaulted arcade support the claim that

the building dates from the mid 16th century.19

EARLY COLONIAL FUSION: YANHUITLAN AND FATHER COBO'S VISIT

In Yanhuitlán, situated in the largest valley of the Mixteca Alta of

Oaxaca, there were certainly buildings associated with high status individuals

at the time of initial contact with the Spanish and these buildings evidently

survived on into the early colonial era and were vividly portrayed clearly

showing their disk frieze ornament, as for example in the case of the Cacique

Nine House seen sitting in front of a large group of his people in the mid

sixteenth century Códice de Yanhuitlán.20

An eyewitness description by the Peruvian Jesuit Father Bernabé Cobo, who

passed through Yanhuitlán in January of 1629, shows that unmistakably European

architectural techniques and luxury features were incorporated into a building

he refers to as the "Casa del cacique:"

In this same town of Yanhuitlán I saw the casa del cacique which

is of the same work as the church, all in stone with a large rectangular patio

at the entrance in which they run bulls, and inside it has two other small

cloisters with stone columns and rooms vaulted with stone with fireplaces in

them such as those at court, certainly a house capable of lodging within it the

royal person.21

The reference to bulls indicates that bullfights were staged in this

enclosure, a recreational activity enjoyed by high status individuals in Spain

as well as the New World, and its mention here was intended to convey how large

the enclosure was. Dr. Kubler referred to this building as "the Tecpan"

and noted that it was built "during the third quarter of the century, at

about the same time the church was in construction."22

Undoubtedly masons who worked on the still spectacular church and

monastery also worked on the Tecpan, or "casa del cacique," and were

able to include the same kinds of distinctly European luxury features in the now

lost building Father Cobo described.23

That this building featured disk frieze ornament may reasonably be assumed

on the basis of the clear record of disk frieze ornament associated with

Nine House as seen in the Códice de Yanhuitlán, a document roughly

contemporary with Cobo's building, and from a surviving example of the use of

disk frieze ornament on what appears to be an early colonial building on the

plaza in Yanhuitlán. Except for

the disks themselves, this building is of adobe, and was neglected, roofless,

and near collapse in August

1993, but its location on the plaza in approximate alignment with the Municipal

Palace indicates its original high status, reinforced and stated publicly by the

disk frieze. In this case the disks are not of the standard double concentric

ring variety or of the flower variety, but rather closely resemble a symbol seen

in Lamina VI of the Códice de Yanhuitlán, which may have been a place glyph,

suggesting that this may have been a residence of a high status individual,

if not the cacique then perhaps a principale of the bario

indicated by this sign.24

SAN JUAN TEPOSCOLULA: A POSSIBLE MODEL

Following his pleasant sojourn in Yanhuitlán, Father Cobo continued

north, passing through San Juan Teposcolula, which he noted was 2 leagues

journey. Dominating a commanding site with a sweeping long view down the valley,

the church of San Juan Teposcolula is an early colonial structure, unusual for

its three aisled basilica plan. Of

special interest here, however, is the residential building immediately south of

the church. San Juan was a visita of San Pedro y San Pablo Teposcolula, and

while it was not a recognized convento, the building next to the church is

clearly intended as a residential facility, perhaps for friars visiting in the

course of their regular liturgical duties in the town. But as Father Cobo's

letter shows, travelers from Oaxaca passed this way en route to México on what

was then, as now, the direct route. San Pedro y San Pablo may have been a larger

population center with a larger church and "accepted" priory, but it

was also a long way from the direct route north-south camino, and notably absent

from Father Cobo's list of points along his route which did include, however,

Tejupan, Tamazulapan, Huahuapan among others that anyone making the same journey

would pass today. Perhaps, then,

the building at San Juan was a stopping point in the Dominican chain from México

to Guatemala, perhaps this building functioned as a hospitality house for

travelers along the chain as well as a residence for friars from the cabecera at

Teposcolula visiting for missionary and liturgical duties.

The residential building at San Juan was quite well built, with standing

walls completely of stone. There is no evidence in what survives of stone

vaulted rooms perhaps because this building was not built for a rich local

cacique, as was the building Cobo described, but rather for occasional use by

friars from the convento at Teposcolula and for mostly mendicant and other

travelers on the camino real. Nevertheless there is a fireplace set neatly into

the wall, as in fashionable buildings back in Spain. The windows are all marked

by carefully cut jambs and the doors all have compression arches carved out of

large stone voussoirs with elaborate mouldings. This is not a rude hut, but an

elegant building suitable for dignified, high status, if not rich, individuals.

It has much in common with another elegant building, this one in San Pedro y San

Pablo Teposcolula, built not for the comfort of Spanish travelers but as the

residence of a Mixtec Queen.

SAN PEDRO Y SAN PABLO TEPOSCOLULA:

CASA DE LA CACICA

At San Juan Teposcolula a road branches southwest toward Tlaxiaco and the

coast from the path followed by Father Cobo. About twelve kilometers from San

Juan along this road is the early colonial town of San Pedro y San Pablo

Teposcolula, justly famous for its spectacular open chapel.

But a lesser known yet equally important building stands on a rise

overlooking this great open chapel and in a direct axial alignment with its

altar.25

It is known locally as the "Casa de la Cacica" and it has much in

common with the building described by Father Cobo and with the Tecpan of Mexico

seen in the Codex Osuna. 26

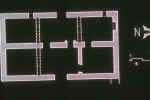

The Casa de la Cacica of Teposcolula is actually a compound including a principal structure still bearing the distinctive disk frieze ornament characteristic of a royal residence, as well as several smaller buildings arranged around a large walled enclosure. Today in this enclosure are kept a small herd of sheep, several cows, a pair of donkeys, some dogs and occasionally a pig or two. If cleared of the debris of some collapsed rooms, a large manure pile, and various agricultural implements, the enclosure might still comfortably host a bull fight. The vestiges of a fountain shows that fresh water was run to the compound and suggest that this enclosure was once landscaped in a luxurious fashion. Another important similarity with the building illustrated in the Codex Osuna is the continuation of the disk frieze on the upper portion of the enclosing wall.

While this detail survives only

in a fragment at the junction of the outer wall with the north east

corner of the principal structure, it is enough to demonstrate the remarkably

close similarity, if not indeed identical conception of this complex and the

Tecpan of México. While the exterior walls of the principal structure at the

Casa de la Cacica survive more or less intact, the perimeter wall of the

enclosure and the rooms joining it have been badly damaged,

by neglect if by nothing else. The masonry at the juncture of the

perimeter wall with the north east corner of the main building strongly suggests

that the main building and the perimeter wall were not built simultaneously, but

that the perimeter wall came after the main building. Although the surviving

fragment of the disk frieze on the perimeter wall is constructed in precisely

the same way as that on the main building, it appears to have been damaged and

then repaired or added on to in a more clumsy execution. A possible explanation

for the absence of the disk frieze elsewhere on the perimeter wall might be that

the work was never finished during the original campaign, perhaps another

casualty of the epidemic of 1576-78. But

there is clear, unmistakable

evidence of the beginning of a frieze on the north wall of the enclosure which,

if the rest had been completed or had survived, would present today a building

compound virtually identical to that seen in the Codex Osuna. And, like the building in the codex, the Casa de la Cacica

makes emphatic use of European technology and taste in the elaborate compression

arches, richly ornamented with carved moldings. Yet another similarity is that

there are out buildings built against the perimeter wall and that there was once

a principal opening in the perimeter wall aligned with the principal door of the

main building. Finally, it is worth noting that on the east and west facades,

that is the long facades, of the Casa de la Cacica the disks appear in

two groups of seven, and in the codex the Tecpan clearly shows the disks

in a single group of seven, two groups of seven may have been too difficult to

render in the reduced scale of the drawing.

Based upon a close examination and comparison of the masonry techniques

employed at the Dominican complex and at the Casa de la Cacica, it appears that

these projects were built more or less concurrently and by the same crews. The

initial program of construction at the Dominican project was terminated before completion in 1579, probably as a result of the

epidemic of 1576-78.27Kubler

also cites this source when he notes that the workers came from surrounding

villages. The crews were assigned to work on another private project, perhaps at

the Casa de la Cacica.28

Concurrent construction of these two projects would parallel the pattern at

Yanhuitlan, which as Cobo noted were "of the same work ."

So it would appear that the Casa de la Cacica was under construction and

nearly completed late in the third quarter of the sixteenth century, paralleling

again the case at Yanhuitlán.

Dr. Kubler refers to the pre-1565 Tecpan of Mexico as a residence and

describes the 1576 Tecpan of Tletelolco as a richly appointed municipal

building. While both would have been used by high status indigenous leaders,

there is a difference between a municipal building and a residence, and

it may well be that this difference had to do with chronology. The building pictured in the Codex Osuna is

clearly identified in a written text immediately above the building as "Tecpa'

calli mexico" or tecpan house of Mexico. The building Father Cobo described

has much in common with that pictured in the Codex Osuna, and with the

description in the Códice...Tlatelolco Dr. Kubler draws on and the surviving

fragment of the arcade.29 Yet in the Yanhuitlán case Father Cobo specifically refers

to this as the Casa del Cacique, which is the same usage as in the case of

Teposcolula except that in Teposcolula it is cast in the feminine: Casa de la

Cacica. A possible explanation for

this may be found in a document dated 1563 from the Viceroy Don Luis de Velasco

in which he officially declared and recognized the legitimate claim to the

cacigazco of Teposcolula by don Felipe de Austria, who was cacique of

Teozacualco but who had married the

natural cacica of Teposcolula and had his living there. Evidently she had been

ruler in her own right prior to the marriage, and this may have been built as

her house, hence Casa de la Cacica.30

If indeed this is the case, then the

residential portion of the complex may have already been in existence by 1563,

and associated with this natural cacica. If

the work on the Dominican complex came to an abrupt end in 1579 and the workers

were assigned to another private project, it may have been an addition to the

Casa de la Cacica, and this may

help explain the obvious discontinuous joint at the northeast corner of the

original building noted above. The

1563 date suggested by this document is reinforced by the certainty of the 1565

date of the illustration in the Codex Osuna, which pictures a building of

precisely the same type. Furthermore, in 1560 the Viceroy don Luis de Velasco

issued a "merced," or grant , authorizing Teposcolula, among other

towns in the Mixteca, to furnish workers, " algunos macehuales," every

week specifically for the personal service to the 'principales,' to work on

their lands and houses.31

So the repartimiento of labor was officially in place for the construction of a

house for the cacica, and work of a very similar kind had already been ongoing

at the Dominican convento down the hill at least since 1550.

Clearly, then, there were by

1560 skilled masons at work in Teposcolula in sufficient numbers to build by

1563 a structure such as the main building at the Casa de la Cacica, even

working in small teams on a rotational basis.

By 1575 don Felipe de

Austria was no longer cacique of Teposcolula, as shown in a document from that

year.32

It appears that don Diego de Mendoza, legitimate son of Diego de Orozco

and María Zárate, caciques of Zoyaltepeque, was himself cacique of Teposcolula

and Tamazulapan, in which towns he lived, and not wishing to live in or be

cacique of Zoyaltepeque, he gave the cacicazgo to his brother, don Bartolomé.

This suggests that don Diego came into possession of Teposcolula by marriage, as

had Don Felipe de Austria before him. Furthermore, by December 1580 another

dynastic change had occurred in Teposcolula, a Domingo de Zúniga had become

"cacique y gobernador," and

he had asked the Viceroy don Lorenzo Suárez de Mendoza for permission to ride

in a saddle with a bridle on a jennet, or small Spanish horse. The Viceroy

granted his request.33

If there was, about 1579, an addition or modification to the Casa de la

Cacica, it may have reflected a transition in the use of the building from a

private residence of the hereditary ruler, or "cacica natural," to a

municipal building. Certainly it appears that

Teposcolula had passed by marriage out of the local ruling family

responsible for the construction of the original main building within the Casa

de la Cacica compound, and after the catastrophic changes brought by the plague

of 1576-78, the building may have ceased to be a residence. There is documentary

evidence suggesting that this may indeed have been the case, and offering a

possible explanation for an interruption in the work on the disk frieze on the

enclosure wall.

On the fifteenth of December 1580 the Viceroy don Lorenzo Suárez de

Mendoza, Conde de Coruña wrote that he had been informed by

"algunos naturales" of Teposcolula that for many days a

Spaniard, one Miguel Sánchez, had been occupying "las casas de la

comunidad" where the Indians had been having their "cabildos y

ayuntamientos" and had been storing their goods and tributes for His

Majesty. The viceroy ordered the Spaniard to vacate the buildings immediately,

and without delay, and without continuing to occupy any part thereof.34

This incident suggests that there was some kind of trouble in the "casas

de la comunidad" at about the time that Domingo de Zúñiga, perhaps newly

possessed of the cacicazgo, was applying for his permit to ride a horse. There

may have been serious disruptions in dynastic continuity resulting from the

epidemic which gave an opening to the opportunistic Spaniard, Miguel Sánchez.

These disruptions may have interrupted construction before the building program

in progress was fully implemented.

THE CASA DE LA CACICA AS PART OF A PLANNED URBAN CONTEXT

The Casa de la Cacica was not an isolated, stand alone architectural

expression of an indigenous ideological agenda. Rather it was part of an

integrated program of urban design openly and obviously intended to demonstrate

and celebrate the continuing prestige of the "cacica natural" of

Teposcolula in the new colonial regime. The relationship between the principal

elements of the built environment in early colonial Teposcolula was not

accidental, but the result of careful planning from the beginning of the

urbanization. The people of San Pedro y San Pablo Teposcolula were persuaded by

the Dominican friars to move from their mountain top redoubt to the floor of the

valley sometime after 1535.35

Indeed, the place name of the community center was known to the Mixtecs before

contact as "Yucu Ndaa, " meaning "on the flat top of the

mountain,"36

which is a good description of the site now known as the "pueblo viejo."

Of course the Dominicans were interested in the construction of a suitable religious center as the focal point for a new Christian life in community. This required a new urban Form. Furthermore, the people of Teposcolula no longer required the protection offered by hill-top locations for their settlements because the long period of armed struggle against the imperial ambitions of the brutal Aztec regime had been ended by the Spanish led popular revolution. The construction of colonial San Pedro y San Pablo Teposcolula was in progress by 1540, and well under way by 1550 when the buildings of the present Dominican convento and open chapel were certainly under construction, partially replacing some of the primitive structures of the initial campaign. By 1550, then, the layout and arrangement of the Dominican complex had been finalized, and with it the layout and arrangement of the traza, or grid of the street plan.

Along with the establishment of the traza went the

distribution of building lots. Certainly

it is no accident that the most prestigious parcel of urban real estate was

reserved for the ruler, with its prominent location overlooking the spectacular

Open Chapel and precisely situated in direct axial alignment with its altar. Nor

would this open and obvious relationship have been lost on villagers, or

pilgrims from other communities, standing in the atrio between the perfectly

aligned Open Chapel and the cacica's house on the hill with its clearly visible

disk frieze, the royal insignia.

These two structures were the two most prestigious, most distinctive

architectural statements in the new town. One was the new ceremonial center for

Christian ritual performance, the other the residence of the hereditary ruler of

the community. The relationship of the buildings suggests a relationship of

their functions. The open chapel is the most spectacular stage for the enactment

of the sacred drama of the Mass ever erected in the New World. It is completely

without European precedent. In its marvelous synthesis of Gothic and Renaissance

forms and techniques it exceeds in its complexity, elegance and stupendous scale

all other open chapels. It was a fabulous architectural concentration of wealth,

of wealth the Mixtecs of Teposcolula kept for themselves, to be permanently,

conspicuously displayed and enjoyed by them, as well as any others who might

come to see their treasure. Such an undertaking required careful planning and

decision making for so vast an allocation of resources. Naturally the Dominican

friars encouraged such lavish undertakings of religious devotion, but without

the approval and support of the indigenous leadership, no such building would

been built. Under compulsion perhaps some other building might have been forced

out of them, but not this building. Not one, but many complex decisions were

made along the way to realizing so unique and so prestigious a temple. And these

were decisions made by the Mixtec leaders. The friars provided design and

technical support and plenty of enthusiastic encouragement, but the Mixtecs

provided the resources. It is not

known if any of the Mixtec leaders of Teposcolula actually labored on the

project themselves, though this seems unlikely. The decisions they made to build

this building, thus were carried out by the general population, on whose backs

the countless blocks of stone were transported. But temple building has never

been easy, neither in pre-Columbian times nor since. At least in the case of

colonial Teposcolula the project was located on the floor of the valley, and not

on a mountain top.

The new open chapel served not only as a locus for the celebration of the

Mass, it also served for the enactment of other, less liturgical, more

pedagogical religious dramas during the holiday festival cycles. The Casa with

its easily recognized disk frieze, basking in the reflected glory and sharing

the prestige of the community's great architectural achievement,

is perfectly located for viewing all the ritual activities performed in

the chapel. Indeed, the relationship of the Casa to the chapel makes complete a

special sacred landscape giving architectural expression to the ceremonial

hierarchy of community life in this new urban environment, vividly reinforced by

the iconographic statement made by the disk frieze. These disks, aparently also

depicting distinclty petalled flowers sacramentally utilized in pre-contact

times, alternate between round and multilobular outline, with a deep central

cavity in both cases.37

The cacica might no longer preside over sacramental ritual performance in

the new Christian town, but it was clear from the spacial relationship of these

two buildings and the iconographic statement made by the disk frieze that from

her commanding residence overlooking the chapel that the "cacica

natural" maintained an important ceremonial role in the life of her people

gathered in the atrio below, at the foot of the great chapel. It is as though

the chapel was built as a backdrop for public religious celebration performed

for the cacica to be seen from her special royal viewing station. The

architecture made this a visible, physical reality, inescapably obvious to

anyone with eyes. The creation of a built environment in which these

relationships were so clearly stated architecturally did not happen by accident,

it was planned this way from the beginning by the indigenous leaders as a

permanent demonstration of their continuing prestige and high status, even in

the colonial regime. They achieved this by deliberately manipulating a new

architecture and urban form, successfully integrating and celebrating symbol

systems well known from the pre-contact world. In this way they perpetuated

their own cultural heritage by integrating it into the new architecture, and

they did this to advance their own ideological agenda. Nor was Teposcolula the

only place in which this architectural manipulation of public ceremonial space

occurred in sixteenth-century México.

OTHER DISK FRIEZE BUILDINGS IN EARLY COLONIAL URBAN CONTEXTS

In 1581 government of Nochixtlan, a town in the Mixteca not far from

Yanhuitlan, prepared a response to a questionnaire circulated by the crown. This

was the Relación de Nochixtlan, and it included a map showing the grid pattern

Traza with the church on a plaza in

the center.38

Nearby three other buildings are shown occupying different blocks near the

center of the town. One of the three buildings is clearly portrayed with a disk

frieze. From the map there is no clear association either by alignment or by

architectural elements between this building with the disk frieze and the

church, except that both are near the center of town and both have friezes,

though in the case of the church the frieze is not a disk frieze but a stepped

geometric pattern. The disk frieze building is located northwest of the church.

It is not yet known if this building survives in any fragmentary form, but given

the steep site of the church and the possibly pre-Hispanic tereplain on which it

is built, it may be that geography prohibited a convenient ceremonial

relationship between these buildings other than proximity. Nevertheless, the

distinctive disk frieze set its

building apart from all the others as plainly on the map as it no doubt did in

the standing building. Further research will investigate possible alignments

with significant topographical elements in this case.

In Mexico City there was

another case of the juxtaposition of a well known and unusual round chapel and a

disk frieze building recorded in an early pictographic document. In a map of

Mexico City attributed to Alonso de Santa Cruz

the Chapel of S. Miguel, built between 1556 and 1558, on Chapultepec Hill

is shown on the hill top but at the bottom of the hill it shows another building

with a disk frieze and a row of arches just as is seen in the Codex Osuna and at

Tlayacapan.39

Unlike in Teposcolula, the chapel is in a higher position, but

nevertheless associated with it at the bottom of a monumental staircase leading

to it is a building combining European arches with traditional pre-Columbian

disk frieze ornament, denoting high status. The buildings are linked by a

staircase along which one can well imagine ceremonial processions. The

unmistakable fact is that the buildings are linked by means of carefully

designed architectural elements and highly visible spacial relationships in

another example of the manipulation of the ceremonial landscape advancing an

indigenous ideological agenda.

The map provided with the 1580 Relación de Zempoala, a colonial site in

what is today the State of Hidalgo, is a fine example of early colonial fusion

of picture writing and map making. The scale and geographic accuracy of the map

are somewhat vague and difficult to interpret. But that several distinct

building types are depicted is abundantly clear, including the large church of

Zampoala, numerous smaller chapels, perhaps of the single cell variety common in

Hidalgo.40

There is also an example of a disk frieze building facing the large church of

Zempoala. The actual spacial relationship of these two buildings cannot be

conclusively confirmed on the basis of this document alone, due to its abstract

and schematic nature. However, further field research may identify the location

of the disk frieze building pictured. Nevertheless, it is safe to say that the

artist responsible for this map clearly sought to carefully portray the large

church and the disk frieze buildings as exceptional cases, given the high level

of uniformity with which all the other buildings are depicted. Furthermore,

these two buildings are the only ones out of the thirty odd buildings shown

which clearly face each other or have anything other than a

purely random relationship. Whatever the reality of their physical

relationship may have been, then, the artist in this case clearly sought to portray them

as though they were in a special spacial relationship for the purpose of the

Relación.

CONCLUSION

The evidence presented here shows that the indigenous leaders in

Teposcolula and other early colonial towns of Mexico deliberately created a new

built environment which emphasized their own continuing prestige by integrated

highly significant symbol systems from their traditional cultural heritage into

a new architectural fusion of Mesoamerican and European forms and techniques

such as is seen in the Casa de la Cacica of Teposcolula and the Tecpan in the

Codex Osuna. The residential building at San Juan Teposcolula shows that the

Mixtec artisans were quite capable of building in a purely European style when

appropriate, and yet they could apply these same skills to other buildings which

through a careful and deliberate fusion of traditional Mixtec form and ornament

gave an altogether different appearance. Thus in the new built environment there

existed side by side buildings fulfilling European needs and other buildings in

a new architectural style advancing an indigenous cultural agenda.

The relationships of the buildings we have examined were not accidental,

but the results of a complex process of decision making and urban planning. On

the basis of standing buildings and documentary evidence we can safely conclude

that in Teposcolula the indigenous leaders were in control of this process. The

artistic creativity of the indigenous people of Teposcolula and other towns and

cities of 16th-century Mexico produced a beautiful new architecture, an

architecture which had never existed before their contact with Europeans. The

evidence shows too, however, that the terrible epidemic of 1576-78 terminated

the development and diffusion of this new architecture before it had fully

matured. Fortunately, the masons at Teposcolula were building for the ages, and

enough has survived to transmit across time physical evidence of a deliberate

process of cultural survival through integration in the early colonial world.

Notes:

1

Otto Adelhofer, ed. Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus 1. Graz, Austria:

Akademische Druk- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1963. See also Jill Leslie Furst. Codex

Vindobonensis Mexicanus 1, A Commentary. Albany: Institute for

Mesoamerican Studies, State University of New York Publication 4, 1978.

Zelia Nuttall, ed. Codex Nuttall: Facsimile of an Ancient Mexican Codex

Belonging to Lord Zouche of Harynworth, England. Cambridge, Mass:

Peabodt Museum, Harvard University, 1902. See also José Luis Melgarejo

Vivanco. Codice Nuttall, tres historias medievales. Veracruz: Comisión

Estatal Conmemorativa del V Centenario del Encuentro de Dos Mundos, 1991.

Cottie A. Burland, ed. Codex Edgerton 2895. Graz, Austria:

Akademische Druk- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1965. [the Codex Sánchez Solís is

also known as Codex Edgerton 2895] For

a n excellent general treatment of the topic

in English with an

extensive bibliography see Mary Elizabeth Smith. Picture Writing

from Ancient Southern Mexico, Mixtec Place Signs and Maps. Norman:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1973.

2

Maarten Jansen. "Las lenguas divinas del México precolonial." Boletin

de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe. 38 (June 1985): 3-14.

3

Donald Robertson. Mexican

Manuscript Painting of the Early Colonial Period. New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1959.

4

Ibid, plate 26, see also his

discussion of the Codex Mendoza: pp. 95-107.

5

Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, compiler; Charles E. Dibble and Arthur

J. O. Anderson, trans. and ed. The Florentine

Codex: General History of the things of New Spain, Book 11-Earthly Things.

Salt Lake City: The School of

American Research and the University of Utah,

1963, pp. 271.

6

See also the recent synthesis treating these buildings and their social

functions in James Lockhart. The Nahuas After the Conquest. Stanford:

Stanford University Press, 1992, pp. 102-110 and elsewhere as noted in the

index.

7

George Kubler. Mexican Architecture of the Sixteenth Century. New

Haven: Yale University Press, 1948, p. 202.

8

Ibid. Kubler cites Relación de Tezcoco NCDHM, III, p. 69.

9

Robertson. Mexican

Manuscript. Plate 33, see also his discussion to the Codex Osuna: pp.

115-122.

10

Kubler. Mexican Architecture. p. 213.

11

Kubler. Mexican Architecture. p. 213-14.

12

Kubler. Mexican Architecture. p. 202.

13

Dr. Susan Webster has emphasized in recent personal communication her

belief, based on her own research in the episcopal archive of Puebla, that

cofradias were actively founded by the mendicant orders much earlier than

has been generally been assumed.

14

Kubler in Mexican Architecture... p. 452-3, notes that the

Franciscans evangelized this area, perhaps before 1547 when the population

was listed, according to Catálogo...Hidalgo, at 820 tributaries. Kubler feels that

the main church in the town, some miles from this small chapel which he does

not mention, was an Augustinian establishment from c. 1560 with links to

Acolman and Yecapixtla. The proximity of this community to the large

Franciscan center at Tula inclines Kubler to believe that

the Franciscan presence in Atotonilco de Tula was dependent on the

larger house at Tula. Kubler notes (p. 484) that the Franciscans were active

at Tula beginning in 1529, built a primitive church there before 1546, and

replaced it with the current edifice after 1550, and the Convento from

1553-61. I am inclined to think that the Cemetary Chapel at Atotonilco de

Tula may be a survival from the initial Franciscan evangelization, and that

it dates from the 1540's. The Augustinian Church in the center of the town

today may have been built as part of a new town built to congregate the

people in an urban environment, not unlike the sequence in Teposcolula.

An old

photograph, probably from the 1930's, appeared in Luis Mac Gregor. El

Plateresco en México. Mexico: Editorial Porrua, 1954, pl. 78.

Considerable deterioration has occurred since this photograph was taken,

calling attention to the need for an immediate preservation intervention at

this important and extremely rare site of transitional architecture.

15

Helen O'Gorman. Mexican Flowering Trees and Plants. México: Ammex

Associados, 1961, p. 154. She writes

"Very few people outside of Mexico know that the dahlia was

originally Mexican, an imperial jewel in the time of Moctezuma, and greatly

loved by him and his cousin, the poet-king Netzahualcoyotl."

16

Concerning the importance of flowers, Serge

Gruzinski in Man-Gods in the Mexican Highlands: Indian Power and Colonial

Society, 1520-1800. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1989 pointed

out that among the elite the source of "heat" or power was

believed to be a divine force infused into the ranks of the pipiltin that

came from Quetzalcoatl and Xiuhtecutli. On page 20 he elaborates as follows:

This fire lodged in the heart of the nobles was far from being a stable

element: the rigors of penance and the discipline of education increased its

intensity, as did contact with jewels, floral offerings, the scent of

flowers, the consumption of the victims' flesh, and even cacao.

This

corresponds with observations recorded by Fernando de Alva Ixtilxochitl and

published in Miguel Leon-Portilla's The Broken Spears, the Aztec Account

of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon Press, 1962,

page 62. From the XIII relacion of Fernando de Alva Ixtilxochitl, a

direct descendent the last king ot Texcoco, there is an account of the

meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma on the causeway. What is particularly

interesting is the note about the flowers which were elaborately prepared

for the ceremonial event, and the importance has to do with connections with

ceremonial flower imagery noted by Gruzinski concerning the building up or

intensifying of the divine fire by proximity to flowers and their scents:

The Spaniards arrived in Xoloco, near the entrance to Tenochtitlán.

That was the end of the march, for they had reached their goal.

Motecuhzoma now arrayed himself in his finery, preparing to go out to

meet them. The other great princes also adorned their persons, as did the

nobles and their chieftains and knights. They all went out to meet the

strangers.

They brought trays heaped with the finest flowers--the flower that

resembles a shield; the flower shaped like a heart; in the center, the

flower with the sweetest aroma; and the fragrant yellow flower, the most

prescious of all. They brought garlands of flowers, and ornaments for the

breast, and necklaces of gold, necklaces hung with rich stones, necklaces

fashioned in the petatillo style.

Thus Motecuhzoma went out to meet them, there in Huitsillan. He

presented many gifts to the Captain and his commanders, those who had come

to make war. He showered gifts upon them and hung flowers around their

necks; he gave them necklaces of flowers and bands of flowers to adorn their

breasts; he set garlands of flowers upon their heads. Then he hung the gold

necklaces around their necks and gave them presents of every sort as gifts

of welcome.

17

Constantino Reyes-Valerio Arte Indocristiano. México:

SEP, 1978. see photo 241. Tequixquiac

lies north of Mexico City on Rt.

167, below Atotonilco de Tula.

18

Smith. Picture Writing. Fig 114, p. 293;

19

Personal interview with the President of the Municipality, August 1992, and

Kubler, Mexican Architecture... p. 520.

20

Wigberto Jiménez Moreno and Salvador Mateos Higuera. Códice de Yanhuitlán.

México: Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, 1940, Lam. II.

21

C. A. Romero, "Dos Cartas inéditas del P. Bernabé Cobo, "

Instituto histórico del Perú, Lima, Revista histórica, tomo VIII-entregas

I-III (1925), 26-50, p. 35. Transcription of this passage by Romero reads as

follows in Spanish:

En este mismo pueblo de Yanguitlan vi la casa del cacique que es de la

misma obra que la iglesia, toda de silleria con grande patio quadrado a la

entrada que se corren en el toros, y dentro tiene otros dos claustros

menores de colunnas de piedra, y las salas de boueda con sus chimeneas en

ellas a lo de corte, casa por cierto capaz de aposentarse en ella la persona

real. Detuueme en aquel pueblo 3 dias en casa de un pariente del Pe. Ror.

recibiendo todo regalo posible: vi en los terminos deste pueblo arboles de

madroños y la plaza del tiene una alameda de alamos blancos.

22Kubler,

Mexican Architecture.... p. 214.

23

There is an oral tradition in Yanhuitlán related to me by the brothers

David and Norberto Jiménez, one of whom was the sacrsitan, that a large set

of standing walls built of mud and rubble south of the Convento complex was

once the Casa del Cacique of Yanhuitlán. This was confirmed by Dr. Ronald

Spores in conversation February 1993. The brothers also related that these

walls once had been clad in fine cut stone, but that the cacique had given

[sold?] this fine stone for

work on the Dominican church. Certainly the current facade of the church is

a later baroque addition, applied directly over the original, probably more

plain, facade. This is apparent when standing in the doorway and looking

straight up. The original door had pyramidal ornament such as is found at

Tlaxiaco and Tejupan, and in several places within the convento at

Teposcolula. The stone of the new facade certainly matches the rest of the

building, and if it is true that the stone cladding of the Casa del Cacique

of Yanhuitlán was removed after Cobo saw it in 1630 for work on the church,

then Cobo would have been correct in his observation that the work on the

Casa was of the same kind of stone as the church. The facade certainly has a

mid seventeenth-century look. Thus, the oral tradition of the Jiménez

brothers may well originate in fact. Stratigraphic excavation within the

high walled compound would reveal much about the early history of colonial

Yanhuitlán, but until now this has not been possible.

24

It is possible that these were originally part of the Casa del Cacique of

Yanhuitlan, and that when that building was stripped of its stone cladding

in the middle of the seventeenth century, these disks were saved and re-used

on an adobe building built in an impoverished

period after the great prosperity of the sixteenth century. Cobo

notes that already by his time the population of Yanhuitlán had fallen from

over 10,000 to about 400.

25

An important aspect of the alignment was pointed out to me by Dr. Annegrete

Vogrin after she saw the presentation of this paper at the 48th

International Congress of Americanists in Stockholm, July 5, 1994. In the

presentation I showed a slide prepared for me by Patrick J. Hannigan using a

digitized 1955 airview photograph in a computer aided design system. I asked

Mr. Hannigan to outline the Open Chapel in blue and the Casa de la Cacica

compound in green and to project a red line from the location of the altar

of the Open Chapel perpendicular to the western facade of the Chapel and see

where the line went. I had supposed that it would bisect the Casa de la

Cacica residence. The projected line approximately bisects the enclosed area

behind the Casa residence, but I was dissapointed that it did not bisect the

actual Casa residence. Rather it appeared to align with the plane of the

south wall of the Casa residence. In spite of my dissappointment, I

nevertheless used this slide for the presentation, and it was precisely this

alignment along the south wall, making the Casa tangent to the axial line,

which attracted Dr.Vogrin's

attention. She has for some years been re-surveying Maya sites, correcting

older site surveys, and her work has

repeatedly revealed precisely this same kind of tangential alignment. What

had been a dissapointment for me was convincing evidence of premeditated

systematic arrangement of monumental architecture consistent with well

established pre-Columbian practice seen in her work. She refered me to her

work Die Architektur von Copan (Honduras). Graz: Akademische Druk-und

Verlagsanstalt, 1982.

26Local

informants agree that this building has been known as the Casa de la

Cacica throughout living memory.

27

Kubler Mexican Architecture.... He gives a general range of

1540-50 for first campaign of building on page 63, in his appendix he notes

on pages 532-3 that building

was still in progress in 1579, but he states

"The Dominicans, after conflict with the encomendero at Yanhuitlan

in 1541, withdrew to Teposcolula, which before that time had been a secular

curacy. When the Dominicans returned to Yanhuitlan ca. 1548-49, the

vicarate of Teposcolula continued under fray Juan Cabrera. A stylized

representation of the church that served the community ca. 1550

occurs in the Códice de Yanhuitlan. This Church is mentioned by

Viceroy Mendoza in 1550. After complaining that the Dominicans were

undertaking many new buildings without proper architectural supervision, he

cites Teposcolula, where the friars had built an inadequate structure

("de muy ruin mezcla) in the hope of attracting the Indians to settle

near the site. This first campaign of building has nothing to do with the

present edifices at Teposcolula, for the unhealthy and humid site described

by the Viceroy does not fit the present location upon the well-drained

slopes of a hill rising to the east of the settlement."

It seems likely

the decision noted in the Actas of the January 1540 provincial meeting to

congregate dispersed indigenous populations may have marked the beginning of

a program to relocate the people of Teposcolula, a process well under way by

1540.

McAndrew. Open

Air Churches.... p. 554: Speaking of the construction of the open chapel

McAndrew states:

Since the work is unfinished, either someone was discouraged with the

work itself, or perhaps discouraged by the plague of '76, or possibly

discouraged when workmen who were to do the final finishings were diverted

to private undertakings in '79.

His endnote 30

on that page refers to Fuentes para la historia del trabajo en Nueva España.

edited by Silvio Zavala and María de Castelo. México (Fondo de Cultura

Económica), 1939, 7 vols., Volume

II, p. 195.

28

Manuel Toussaint Paseos Coloniales México: UNAM, 1939, pp.26-27, Colonial

Art In Mexico Austin: University of Texas Press, 1967, p. 61. Toussaint

felt that the existing church was later than the open air chapel which he

thought was built between 1550 and 1575, while suggesting that some of the

existing sculptural elements of the church facade may have come from an

earlier building. John McAndrew. Open Air Churches of Sixteenth-Century

Mexico. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965. McAndrew points out

on page 544 that "a monastery and a church must have been acceptable

enough to the Provincial Chapter by 1561, since that year they chose to meet

there." He states his assumption that the open chapel was probably

built between 1561 and the plague year of 1576. On page 547 he adds "No

more skillful vault had been built in the Americas...It was perhaps the

finest example in the New World of Medieval craftsmanship on a grand scale

which has survived to out time." McAndrew points out similarities of

the work with illustrations of various editions of Vitruvius, Serlio and

Diego de Sagredo. Mullen, Dominican Architecture. Mullen on pages

128-138 describes events surrounding its construction, and suggests that an

"old" chapel, "there had to be one," was demolished and

the "new" open air chapel must have begun after Fray Marin

returned to Teposcolula in 1548. He identifies a Fray Marin as its architect

and notes that it was his masterpiece.

29

Kubler. Mexican Architecture.... p. 185, see note 232. He cites

"Códice...Tlatelolco, " Investigaciones históricas, 1,

no. 3 (1939).

30

Ronald Spores. Coleccion de documentos del archivo general de la

nacion para la etnohistoria de la Mixteca de Oaxaca en el siglo XVI.

Nashville: Vanderbilt University Publications in Anthropology, 1992, p. 31,

Document 61, "Mandamiento de amparo a don Felipe de Castilla de

Teozacuaco en el cargo sin que se haga novedad a la relacion de Alonso

Canseco. Dr. Spores' typescript transcription of the relevant passage

follows:

...Por cuanto don Felipe de Austria cacique del pueblo de Teozacualco

está por mí declarado por cacique y gobernador de la provincia de

Tepozcolula porque se casó legíimamente con cacica natural y a causa de

tener su vivienda en la dicha provincia de Tepozcolula con su mujer se teme

que los del dicho pueblo de Tezoacualco [sic] era novedad a no admitirle por

tal su cacique y gobernador natural y me pidió le mandese dar mi

mandamiento de amparo para que fuese tenido y obedecido por tal su cacique y

gobernado del dicho pueblo de Teozacualco como lo era de Tepozcolula. ...

31

Spores. Coleccion de documentos....p. 22, Document 45, "Sobre

que en cada pueblo de la Misteca se repartan cada semana algunos Indios para

beneficiar las tierras parajes y reparar sus casas, pagandoles su trabajo.

The document is damaged and incomplete, but it specifies that the workers

shall be paid, but it less clear on how many workers are to be provided.

32

Spores. Coleccion de documentos....p 52, Document 107,

"Diego de Mendoza y Diego de Orozco sobre el cacicazgo de Zoyaltepec."

Dr. Spores' typescript transcription of the relevant passage follows:

E por ende, por virtud de la dicha licencia al dicho don Diego de

Mendoza, dada e concedida, dijo que de su grado y buena voluntad sin premia

ni fuerza que le sea hecho en pública ni en secreta. E que por cuanto él

es hijo legítimo de don Diego de Orozco, e de doña María Zárate su legítima

mujer a quien podría suceder el cacicazgo e señorío del pueblo de

Zoyaltepeque como hijo mayor del dicho don Diego, su padre. E porque él

tiene el cacicazgo e senorío del pueblo de Tamazulapa, a de Teposcolula y

vive y reside en los dichos pueblos, en los cuales goza de los dichos

cacicazgos, e no puede asistir en el dicho pueblo de Zoyaltepeque a gozar

del dicho cacicazgo, e copnformer a

la dicha su costumbre e faltando el hijo mayor, yéndose a casar y vivir en

otro pueblo e cacicazgo, sucede en él, segundo hijo, que por aquella vía e

forma que de derecho mejor lugar haya él cedía y traspasaba y renunciaba e

renunció el aución que a él tiene y le pertenece y puede perteneder en

qualquier manera a don Bartolomé de Orozco....

33

Spores. Coleccion de documentos....p68, Document 146,

"Domingo de Zuñiga, Cacique de Teposcolula."

34

Spores. Coleccion de documentos.... p. 69, Document 148, "Los

Naturales de Teposcolula." Dr.

Spores' typescript transcription

of the document follows:

Don Lorenzo Suárez de Mendoza, etc. Hago Saber a vos el alcalde mayor

de la provincia de Teposcolula que algunos naturales de ella me ha sido

hecha relación, que un Miguel Sánchez español, so color de ser suegro del

escribano propietario de la dicha provincia y pueblo de Teposcolula, tiene

ocupadas muchos días las casas de la comunidad de él, donde los dichos

naturales han de haber sus cabildos y ayuntamientos y recoger sus bienes y

tributos de Su Magestad, pidiendo se la mandase desocupar. Y por mi visto,

por la presente os mando que luego que os sea mostrado compeláis al dicho

Miguel Sánchez deje a los naturales del dicho pueblo de Teposcolula libres

y desembarazadas las casas de su comunidad, no dejando ocupada en ellas

parte alguna. Lo cual haced y complid sin dilación ni remisión. Hecho en México

a 15 días del mes de diciembre de 1580 años. El Conde de Coruña. Por

mandado de Su Execencia, Martín López de Gaona.

35

The exact date of first Dominican arrival in Teposcolula remains uncertain.

Robert Mullen in Dominican Architecture in Oaxaca. Phoenix: Center

for Latin American Studies, 1975, p. 31, demonstrates that a Dominican

house, founded after 1535 by Fray Betanzos, was "accepted" or

recognized by the 1538 Provincial chapter meeting of the order.

36

Raul Alavez. Toponimia Mixteca. Tlalpan, México: Ediciones de La

Casa Chata, 1988, p. 92.

37

My ongoing research aims at positively identifying flowers corresponding to

the explicit forms depicted in the disks, and identifying patterns in the

iconographic-ideological use of disk friezes throughout post-conquest

Mexico. However on 5 November 1994 I showed Dr. Leslie Garay slides of the

disks on the Casa de la Cacica, the church at Yolomecatl a town between

Teposcolula and Tlaxiaco, and on the chapel at Atotonilco de Tula, and also

slides of the disks found on the tower of the church at Tlamanalco and on

the arm of the statue of the Flower Prince, Xochipili, discovered in

Tlalmanalco in 1885. Dr. Garay

a botonist long familiar with tropical plants and recently retired from the

Botanical Museum of Harvard University,

was a longtime colleague and research associate of Richard Schulte

who published frequently on the topic of psychotropic and narcotic plants

used in aboriginal American religious ritual. Dr Garay was also a close

friend and colleague of Gordon Wasson, well known for his work with

hallucinogenic mushrooms in Native American cults. Drs. Garay and Schulte

often traveled and worked together in the field in many areas of Latin

America including Mexico. Looking at the alternating disks on the Casa de la

Cacica he confirmed my suspicions when he said without hesitation that the

one with spikes is datura and the other is morning glory, both much used in

ritual intoxication in pre-conquest Mexico. He said both were abundantly

present in the flora of Oaxaca of the period of contact. He pointed to the